|

|

|

|

All About Thanksgiving |

|

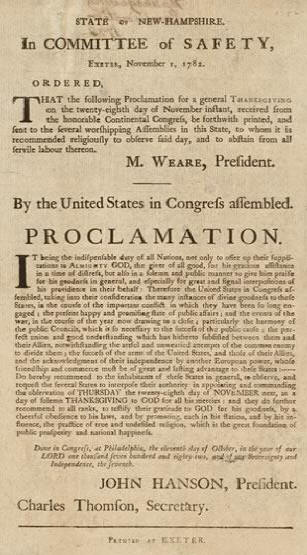

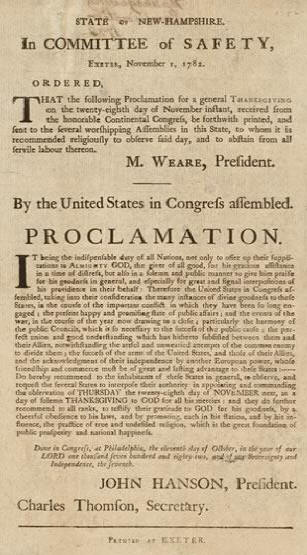

Thanksgiving Proclamation |

The State of New Hampshire, in Committee of Safety, Exeter, November 1, 1782Ordered, that the following proclamation for a general Thanksgiving on the 28th day of November be received from the honorable Continental Congress, and forthwith printed and sent to the several worshipping Assemblies in this State, to whom it is recommended religiously to observe said day, and to abstain from all servile labour thereon. M. WEARE, President By the United States in Congress assembled.

PROCLAMATION.

IT being the indispensable duty of all Nations, not only to offer up their supplications to ALMIGHTY GOD, the giver of all good, for his gracious assistance in a time of distress, but also in a solemn and public manner to give him praise for his goodness in general, and especially for great and signal interpositions of his providence in their behalf:

Therefore the United States in Congress assembled, taking into their consideration the many instances of divine goodness to these States, in the course of the important conflict in which they have been so long engaged; the present happy and promising state of public affairs; and the events of the war, in the course of the year now drawing to a close; particularly the harmony of the public Councils, which is so necessary to the success of the public cause; the perfect union and good understanding which has hitherto subsisted between them and their Allies, notwithstanding the artful and unwearied attempts of the common enemy to divide them; the success of the arms of the United States, and those of their Allies, and the acknowledgment of their independence by another European power, whose friendship and commerce must be of great and lasting advantage to these States:---

Do hereby recommend to the inhabitants of these States in general, to observe, and request the several States to interpose their authority in appointing and commanding the observation of THURSDAY the twenty-eight day of NOVEMBER next, as a day of solemn THANKSGIVING to GOD for all his mercies: and they do further recommend to all ranks, to testify to their gratitude to GOD for his goodness, by a cheerful obedience of his laws, and by promoting, each in his station, and by his influence, the practice of true and undefiled religion, which is the great foundation of public prosperity and national happiness.

Done in Congress, at Philadelphia, the eleventh day of October, in the year of our LORD one thousand seven hundred and eighty-two, and of our Sovereignty and Independence, the seventh.

JOHN HANSON, President.

Charles Thomson, Secretary.

PRINTED AT EXETER. The Thanksgiving Proclamation and the Proclamation Image are Courtesy of The Library of Congress.

back to top

|

The First Thanksgiving

In 1621, the Plymouth

colonists and Wampanoag

Indians shared an autumn

harvest feast which is

acknowledged today as one of

the first Thanksgiving

celebrations in the

colonies. This harvest meal

has become a symbol of

cooperation and interaction

between English colonists

and Native Americans.

Although this feast is

considered by many to the

very first Thanksgiving

celebration, it was actually

in keeping with a long

tradition of celebrating the

harvest and giving thanks

for a successful bounty of

crops. Native American

groups throughout the

Americas, including the

Pueblo, Cherokee, Creek and

many others organized

harvest festivals,

ceremonial dances, and other

celebrations of thanks for

centuries before the arrival

of Europeans in North

America.

Historians have also

recorded other ceremonies of

thanks among European

settlers in North America,

including British colonists

in Berkeley Plantation,

Virginia. At this site near

the Charles River in

December of 1619, a group of

British settlers led by

Captain John Woodlief knelt

in prayer and pledged

"Thanksgiving" to God for

their healthy arrival after

a long voyage across the

Atlantic. This event has

been acknowledged by some

scholars and writers as the

official first Thanksgiving

among European settlers on

record. Whether at Plymouth,

Berkeley Plantation, or

throughout the Americas,

celebrations of thanks have

held great meaning and

importance over time. The

legacy of thanks, and

particularly of the feast,

have survived the centuries

as people throughout the

United States gather family,

friends, and enormous

amounts of food for their

yearly Thanksgiving meal.

What Was Actually on the

Menu?

What foods topped the table

at the first harvest feast?

Historians aren't completely

certain about the full

bounty, but it's safe to say

the pilgrims weren't

gobbling up pumpkin pie or

playing with their mashed

potatoes. Following is a

list of the foods that were

available to the colonists

at the time of the 1621

feast. However, the only two

items that historians know

for sure were on the menu

are venison and wild fowl,

which are mentioned in

primary sources. The most

detailed description of the

"First Thanksgiving" comes

from Edward Winslow from

A Journal of the Pilgrims at

Plymouth, in 1621:

"Our harvest being gotten

in, our governor sent four

men on fowling, that so we

might after a special manner

rejoice together after we

had gathered the fruit of

our labors. They four in one

day killed as much fowl as,

with a little help beside,

served the company almost a

week. At which time, among

other recreations, we

exercised our arms, many of

the Indians coming amongst

us, and among the rest their

greatest king Massasoit,

with some ninety men, whom

for three days we

entertained and feasted, and

they went out and killed

five deer, which they

brought to the plantation

and bestowed upon our

governor, and upon the

captain, and others. And

although it be not always so

plentiful as it was at this

time with us, yet by the

goodness of God, we are so

far from want that we often

wish you partakers of our

plenty."

Did you know

that lobster, seal and swans

were on the Pilgrims' menu?

Seventeenth Century Table

Manners:

The pilgrims didn't use

forks; they ate with spoons,

knives, and their fingers.

They wiped their hands on

large cloth napkins which

they also used to pick up

hot morsels of food. Salt

would have been on the table

at the harvest feast, and

people would have sprinkled

it on their food. Pepper,

however, was something that

they used for cooking but

wasn't available on the

table.

In the seventeenth century,

a person's social standing

determined what he or she

ate. The best food was

placed next to the most

important people. People

didn't tend to sample

everything that was on the

table (as we do today), they

just ate what was closest to

them.

Serving in the seventeenth

century was very different

from serving today. People

weren't served their meals

individually. Foods were

served onto the table and

then people took the food

from the table and ate it.

All the servers had to do

was move the food from the

place where it was cooked

onto the table.

Pilgrims didn't eat in

courses as we do today. All

of the different types of

foods were placed on the

table at the same time and

people ate in any order they

chose. Sometimes there were

two courses, but each of

them would contain both meat

dishes, puddings, and

sweets.

More Meat, Less Vegetables

Our modern Thanksgiving

repast is centered around

the turkey, but that

certainly wasn't the case at

the pilgrims's feasts. Their

meals included many

different meats. Vegetable

dishes, one of the main

components of our modern

celebration, didn't really

play a large part in the

feast mentality of the

seventeenth century.

Depending on the time of

year, many vegetables

weren't available to the

colonists.

The pilgrims probably didn't

have pies or anything sweet

at the harvest feast. They

had brought some sugar with

them on the Mayflower but by

the time of the feast, the

supply had dwindled. Also,

they didn't have an oven so

pies and cakes and breads

were not possible at all.

The food that was eaten at

the harvest feast would have

seemed fatty by 1990's

standards, but it was

probably more healthy for

the pilgrims than it would

be for people today. The

colonists were more active

and needed more protein.

Heart attack was the least

of their worries. They were

more concerned about the

plague and pox.

Surprisingly Spicy Cooking

People tend to think of

English food at bland, but,

in fact, the pilgrims used

many spices, including

cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg,

pepper, and dried fruit, in

sauces for meats. In the

seventeenth century, cooks

did not use proportions or

talk about teaspoons and

tablespoons. Instead, they

just improvised. The best

way to cook things in the

seventeenth century was to

roast them. Among the

pilgrims, someone was

assigned to sit for hours at

a time and turn the spit to

make sure the meat was

evenly done.

Since the pilgrims and

Wampanoag Indians had no

refrigeration in the

seventeenth century, they

tended to dry a lot of their

foods to preserve them. They

dried Indian corn, hams,

fish, and herbs.

Dinner for Breakfast:

Pilgrim Meals:

The biggest meal of the day

for the colonists was eaten

at noon and it was called

noonmeat or dinner. The

housewives would spend part

of their morning cooking

that meal. Supper was a

smaller meal that they had

at the end of the day.

Breakfast tended to be

leftovers from the previous

day's noonmeat.

In a pilgrim household, the

adults sat down to eat and

the children and servants

waited on them. The foods

that the colonists and

Wampanoag Indians ate were

very similar, but their

eating patterns were

different. While the

colonists had set eating

patterns—breakfast, dinner,

and supper—the Wampanoags

tended to eat when they were

hungry and to have pots

cooking throughout the day.

Source: Kathleen Curtin,

Food Historian at Plymouth

Plantation

back to top

|

|

When is Thanksgiving |

|

Each year in America Thanksgiving

falls on the fourth Thursday of November. Most years this is the

last Thursday in November, but in some years there are five

Thursdays in November, and then Thanksgiving falls on the second

to last Thursday. |

|

Here are the dates of

Thanksgiving Thursday from 2009 through 2013.

|

Thanksgiving 2009: Thursday, November 26

Thanksgiving 2010: Thursday, November 25

Thanksgiving 2011: Thursday, November 24

Thanksgiving 2012: Thursday, November 22

Thanksgiving 2013: Thursday, November 28

back to top

|

|

The Pilgrims' Menu

Foods

That May Have Been on the Menu |

|

Seafood: |

Cod, Eel,

Clams, Lobster |

|

Wild Fowl: |

Wild Turkey, Goose,

Duck, Crane, Swan, Partridge, Eagles |

|

Meat: |

Venison,

Seal |

|

Grain: |

Wheat Flour,

Indian Corn |

|

Vegetables: |

Pumpkin, Peas, Beans,

Onions, Lettuce, Radishes, Carrots |

|

Fruit: |

Plums,

Grapes |

|

Nuts: |

Walnuts,

Chestnuts, Acorns |

|

Herbs and

Seasonings: |

Olive Oil, Liverwort,

Leeks, Dried Currants, Parsnips |

|

|

What Was Not on the Menu |

|

The

following foods, all considered staples of the modern

Thanksgiving meal, didn't appear on the pilgrims's first feast

table: |

|

Ham: |

There is no

evidence that

the colonists

had butchered a

pig by this

time, though

they had brought

pigs with them

from England. |

|

Sweet

Potatoes/Potatoes: |

These were

not common. |

|

Corn on

the Cob: |

Corn was kept

dried out at

this time of

year. |

|

Cranberry Sauce: |

The colonists

had cranberries

but no sugar at

this time. |

|

Pumpkin Pie: |

It's not a

recipe that

exists at this

point, though

the pilgrims had

recipes for

stewed pumpkin. |

|

Chicken/Eggs |

We know that

the colonists

brought hens

with them from

England, but

it's unknown how

many they had

left at this

point or whether

the hens were

still laying.

Milk:

|

|

Milk: |

No cows had

been aboard the

Mayflower,

though it's

possible that

the colonists

used goat milk

to make cheese. |

Source: Kathleen Curtin,

Food Historian at Plymouth

Plantation.

|

|

back to top |

|

Thanksgiving Fun Facts |

Over the Years

Though many competing claims

exist, the most familiar

story of the first

Thanksgiving took place in

Plymouth Colony, in

present-day Massachusetts,

in 1621. More than 200 years

later, President Abraham

Lincoln declared the final

Thursday in November as a

national day of

thanksgiving. Congress

finally made Thanksgiving

Day an official national

holiday in 1941.

Sarah Josepha Hale, the

enormously influential

magazine editor and author

who waged a tireless

campaign to make

Thanksgiving a national

holiday in the mid-19th

century, was also the author

of the classic nursery rhyme

"Mary Had a Little Lamb."

In 2001, the U.S. Postal

Service issued a

commemorative Thanksgiving

stamp. Designed by the

artist Margaret Cusack in a

style resembling traditional

folk-art needlework, it

depicted a cornucopia

overflowing with fruits and

vegetables, under the phrase

"We Give Thanks."

On the Roads

Despite record-high gas

prices (more than $3.00 per

gallon) in 2007, the

American Automobile

Association (AAA) estimated

that 38.7 million Americans

would travel 50 miles or

more from home for the

Thanksgiving holiday, a

slight increase (1.5

percent) over the previous

year.

Of those Americans traveling

for Thanksgiving in 2007,

approximately 80 percent

(31.2 million) were expected

to go by motor vehicle, 12.1

percent (4.7 million) by

airplane and the rest (2.8

million) by train, bus or

other mode of

transportation.

On the Table

According to the U.S. Census

Bureau, Minnesota is the top

turkey-producing state in

America, with a planned

production total of 49

million in 2008. Just six

states, Minnesota, North

Carolina, Arkansas,

Virginia, Missouri, and

Indiana will probably

produce two-thirds of the

estimated 271 million birds

that will be raised in the

U.S. this year.

The National Turkey

Federation estimated that 46

million turkeys, one fifth

of the annual total of 235

million consumed in the

United States in 2007, were

eaten at Thanksgiving.

In a survey conducted by the

National Turkey Federation,

nearly 88 percent of

Americans said they eat

turkey at Thanksgiving. The

average weight of turkeys

purchased for Thanksgiving

is 15 pounds, which means

some 690 million pounds of

turkey were consumed in the

U.S. during Thanksgiving in

2007.

The cranberry is one of only

three fruits. The others are

the blueberry and the

Concord grape—that are

entirely native to North

American soil, according to

the Cape Cod Cranberry

Growers' Association.

According to the Guinness

Book of World Records, the

largest pumpkin pie ever

baked weighed 2,020 pounds

and measured just over 12

feet long. It was baked on

October 8, 2005 by the New

Bremen Giant Pumpkin Growers

in Ohio, and included 900

pounds of pumpkin, 62

gallons of evaporated milk,

155 dozen eggs, 300 pounds

of sugar, 3.5 pounds of

salt, 7 pounds of cinnamon,

2 pounds of pumpkin spice

and 250 pounds of crust.

Around the Country

Three towns in the U.S. take

their name from the

traditional Thanksgiving

bird, including Turkey,

Texas (pop. 465); Turkey

Creek, Louisiana (pop. 363);

and Turkey, North Carolina

(pop. 270).

Originally known as Macy's

Christmas Parade to signify

the launch of the Christmas

shopping season. The first

Macy's Thanksgiving Day

Parade took place in New

York City in 1924. It was

launched by Macy's employees

and featured animals from

the Central Park Zoo. Today,

some 3 million people attend

the annual parade and

another 44 million watch it

on television.

Tony Sarg, a children's book

illustrator and puppeteer,

designed the first giant hot

air balloons for the Macy's

Thanksgiving Day Parade in

1927. He later created the

elaborate mechanically

animated window displays

that grace the façade of the

New York store from

Thanksgiving to Christmas.

Snoopy has appeared as a

giant balloon in the Macy's

Thanksgiving Day Parade more

times than any other

character in history. As the

Flying Ace, Snoopy made his

sixth appearance in the 2006

parade.

The first time the Detroit

Lions played football on

Thanksgiving Day was in

1934, when they hosted the

Chicago Bears at the

University of Detroit

stadium, in front of 26,000

fans. The NBC radio network

broadcast the game on 94

stations across the country

the first national

Thanksgiving football

broadcast. Since that time,

the Lions have played a game

every Thanksgiving (except

between 1939 and 1944); in

1956, fans watched the game

on television for the first

time.

back to top

|

|

Mayflower Myths |

|

"The

reason that we have so many myths associated with Thanksgiving

is that it is an invented tradition. It doesn't originate in any

one event. It is based on the New England puritan Thanksgiving,

which is a religious Thanksgiving, and the traditional harvest

celebrations of England and New England and maybe other ideas

like commemorating the pilgrims. All of these have been gathered

together and transformed into something different from the

original parts."– James W. Baker - Historian |

Myth:

The first Thanksgiving was

in 1621 and the pilgrims

celebrated it every year

thereafter.

Fact:

The first feast wasn't

repeated, so it wasn't the

beginning of a tradition. In

fact, the colonists didn't

even call the day

Thanksgiving. To them, a

thanksgiving was a religious

holiday in which they would

go to church and thank God

for a specific event, such

as the winning of a battle.

On such a religious day, the

types of recreational

activities that the pilgrims

and Wampanoag Indians

participated in during the

1621 harvest feast--dancing,

singing secular songs,

playing games--wouldn't have

been allowed. The feast was

a secular celebration, so it

never would have been

considered a thanksgiving in

the pilgrims minds.

Myth:

The original Thanksgiving

feast took place on the

fourth Thursday of November.

Fact:

The original feast in 1621

occurred sometime between

September 21 and November

11. Unlike our modern

holiday, it was three days

long. The event was based on

English harvest festivals,

which traditionally occurred

around the 29th of

September. After that first

harvest was completed by the

Plymouth colonists, Gov.

William Bradford proclaimed

a day of thanksgiving and

prayer, shared by all the

colonists and neighboring

Indians. In 1623 a day of

fasting and prayer during a

period of drought was

changed to one of

thanksgiving because the

rain came during the

prayers. Gradually the

custom prevailed in New

England of annually

celebrating thanksgiving

after the harvest.

During the

American Revolution a yearly

day of national thanksgiving

was suggested by the

Continental Congress. In

1817 New York State adopted

Thanksgiving Day as an

annual custom, and by the

middle of the 19th century

many other states had done

the same. In 1863 President

Abraham Lincoln appointed a

day of thanksgiving as the

last Thursday in November,

which he may have correlated

it with the November 21,

1621, anchoring of the

Mayflower at Cape Cod.

Since then, each president

has issued a

Thanksgiving Day

proclamation.

President Franklin D.

Roosevelt set the date for

Thanksgiving to the fourth

Thursday of November in 1939

(approved by Congress in

1941)

Myth:

The pilgrims wore only black

and white clothing. They had

buckles on their hats,

garments, and shoes.

Fact:

Buckles did not come into

fashion until later in the

seventeenth century and

black and white were

commonly worn only on Sunday

and formal occasions. Women

typically dressed in red,

earthy green, brown, blue,

violet, and gray, while men

wore clothing in white,

beige, black, earthy green,

and brown.

Myth:

The pilgrims brought

furniture with them on the

Mayflower.

Fact:

The only furniture that the

pilgrims brought on the

Mayflower was chests and

boxes. They constructed

wooden furniture once they

settled in Plymouth.

Myth:

The Mayflower was headed for

Virginia, but due to a

navigational mistake it

ended up in Cape Cod

Massachusetts.

Fact:

The Pilgrims were in fact

planning to settle in

Virginia, but not the

modern-day state of

Virginia. They were part of

the Virginia Company, which

had the rights to most of

the eastern seaboard of the

U.S. The pilgrims had

intended to go to the Hudson

River region in New York

State, which would have been

considered "Northern

Virginia," but they landed

in Cape Cod instead.

Treacherous seas prevented

them from venturing further

south.

back to top

|

|

How Much Do

You Know About Thanksgiving? |

|

1. Fact or Fiction:

Thanksgiving is held on the final Thursday of November each

year. |

|

Fiction.

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln designated the last Thursday

in November as a national day of thanksgiving. However, in 1939,

after a request from the National Retail Dry Goods Association,

President Franklin Roosevelt decreed that the holiday should

always be celebrated on the fourth Thursday of the month (and

never the occasional fifth, as occurred in 1939) in order to

extend the holiday shopping season by a week. The decision

sparked great controversy, and was still unresolved two years

later, when the House of Representatives passed a resolution

making the last Thursday in November a legal national holiday.

The Senate amended the resolution, setting the date as the

fourth Thursday, and the House eventually agreed. |

|

2. Fact or Fiction:

One of America's Founding Fathers thought the turkey should be

the national bird of the United States. |

|

Fact.

In a letter to his daughter sent in 1784, Benjamin Franklin

suggested that the wild turkey would be a more appropriate

national symbol for the newly independent United States than the

bald eagle (which had earlier been chosen by the Continental

Congress). He argued that the turkey was "a much more

respectable Bird," "a true original Native of America," and

"though a little vain & silly, a Bird of Courage." |

|

3. Fact or Fiction:

In 1863, Abraham Lincoln became the first American president to

proclaim a national day of thanksgiving. |

|

Fiction.

George Washington, John Adams and James Madison all issued

proclamations urging Americans to observe days of thanksgiving,

both for general good fortune and for particularly momentous

events (the adoption of the U.S. Constitution, in Washington's

case; the end of the War of 1812, in Madison's). |

|

4. Fact or Fiction:

Macy's was the first American department store to sponsor a

parade in celebration of Thanksgiving. |

|

Fiction.

The Philadelphia department store Gimbel's had sponsored a

parade in 1920, but the Macy's parade, launched four years

later, soon became a Thanksgiving tradition and the standard

kickoff to the holiday shopping season. The parade became ever

more well-known after it featured prominently in the hit film

Miracle on 34th Street (1947), which shows actual footage of the

1946 parade. In addition to its famous giant balloons and

floats, the Macy's parade features live music and other

performances, including by the Radio City Music Hall Rockettes

and cast members of well-known Broadway shows. |

|

5. Fact or Fiction:

Turkeys are slow-moving birds that lack the ability to fly. |

|

Fiction (kind of).

Domesticated turkeys (the type eaten on Thanksgiving) cannot

fly, and their pace is limited to a slow walk. Female domestic

turkeys, which are typically smaller and lighter than males, can

move somewhat faster. Wild turkeys, on the other hand, are much

smaller and more agile. They can reach speeds of up to 20-25

miles per hour on the ground and fly for short distances at

speeds approaching 55 miles per hour. They also have better

eyesight and hearing than their domestic counterparts. |

|

6. Fact or Fiction:

Native Americans used cranberries, now a staple of many

Thanksgiving dinners, for cooking as well as medicinal purposes. |

|

Fact.

According to the Cape Cod Cranberry Growers' Association, one of

the country's oldest farmers' organizations, Native Americans

used cranberries in a variety of foods, including "pemmican" (a

nourishing, high-protein combination of crushed berries, dried

deer meat and melted fat). They also used it as a medicine to

treat arrow punctures and other wounds and as a dye for fabric.

The Pilgrims adopted these uses for the fruit and gave it a

name—"craneberry"—because its drooping pink blossoms in the

spring reminded them of a crane. |

|

7. Fact or Fiction:

The movement of the turkey inspired a ballroom dance. |

|

Fact.

The turkey trot, modeled on that bird's characteristic short,

jerky steps, was one of a number of popular dance styles that

emerged during the late 19th and early 20th century in the

United States. The two-step, a simple dance that required little

to no instruction, was quickly followed by such dances as the

one-step, the turkey trot, the fox trot and the bunny hug, which

could all be performed to the ragtime and jazz music popular at

the time. The popularity of such dances spread like wildfire,

helped along by the teachings and performances of exhibition

dancers like the famous husband-and-wife team Vernon and Irene

Castle. |

|

8. Fact or Fiction:

On Thanksgiving Day in 2007, two turkeys earned a trip to Disney

World. |

|

Fact.

On November 20, 2007, President George W. Bush granted a

"pardon" to two turkeys, named May and Flower, at the 60th

annual National Thanksgiving Turkey presentation, held in the

Rose Garden at the White House. The two turkeys were flown to

Orlando, Florida, where they served as honorary grand marshals

for the Disney World Thanksgiving Parade. The current tradition

of presidential turkey pardons began in 1947, under Harry

Truman, but the practice is said to have informally begun with

Abraham Lincoln, who granted a pardon to his son Tad's pet

turkey. |

|

9. Fact or Fiction:

Turkey contains an amino acid that makes you sleepy. |

|

Fact.

Turkey does contain the essential amino acid tryptophan, which

is a natural sedative, but so do a lot of other foods, including

chicken, beef, pork, beans and cheese. Though many people

believe turkey's tryptophan content is what makes many people

feel sleepy after a big Thanksgiving meal, it is more likely the

combination of fats and carbohydrates most people eat with the

turkey, as well as the large amount of food (not to mention

alcohol, in some cases) consumed, that makes most people feel

like following their meal up with a nap. |

|

10. Fact or Fiction:

The tradition of playing or watching football on Thanksgiving

started with the first National Football League game on the

holiday in 1934. |

|

Fiction.

The American tradition of college football on Thanksgiving is

pretty much as old as the sport itself. The newly formed

American Intercollegiate Football Association held its first

championship game on Thanksgiving Day in 1876. At the time, the

sport resembled something between rugby and what we think of as

football today. By the 1890s, more than 5,000 club, college and

high school football games were taking place on Thanksgiving,

and championship match-ups between schools like Princeton and

Yale could draw up to 40,000 fans. The NFL took up the tradition

in 1934, when the Detroit Lions (recently arrived in the city

and renamed) played the Chicago Bears at the University of

Detroit stadium in front of 26,000 fans. Since then, the Lions

game on Thanksgiving has become an annual event, taking place

every year except during the World War II years (1939–1944).

back to top |